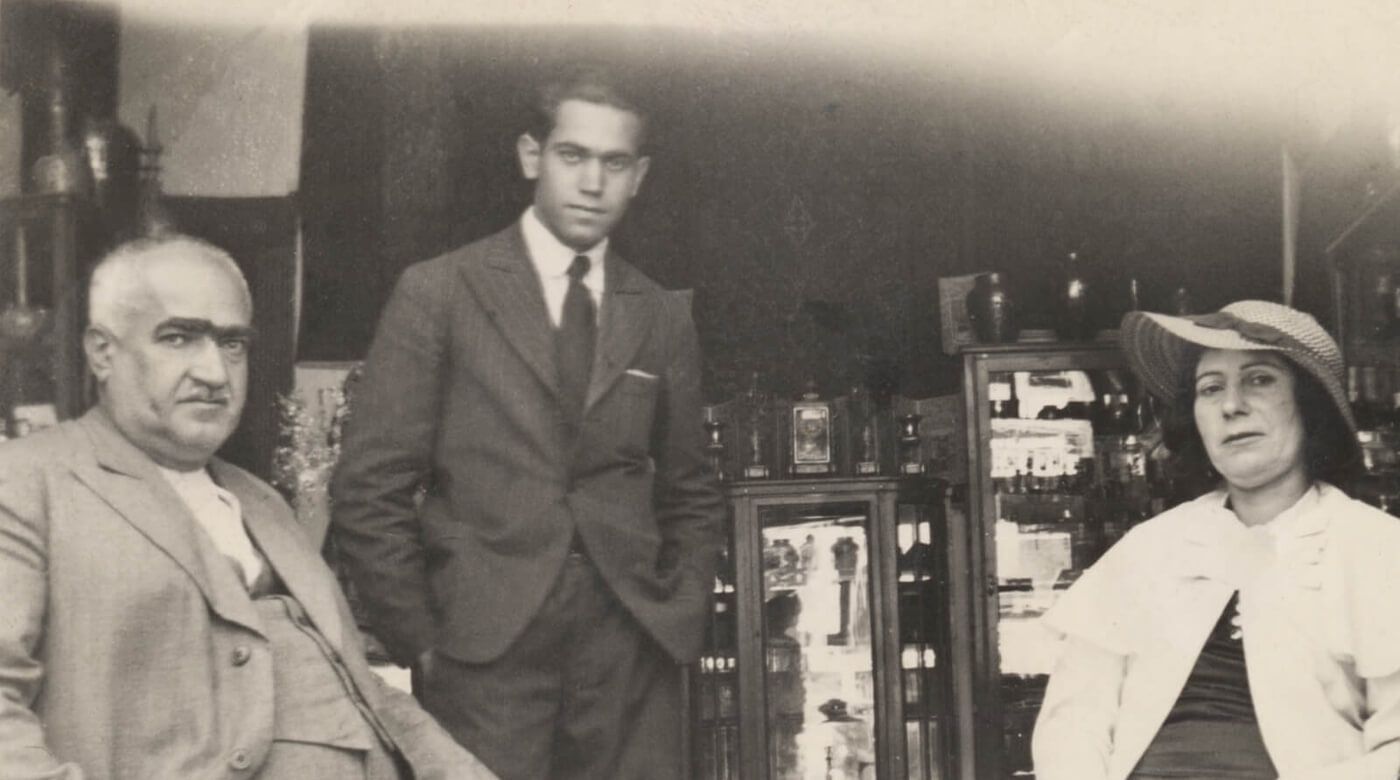

Yervant

Yervant was a very old man, or at least that’s how I remember him. He was Persian and Armenian, and he had once been wealthy. I remember Yervant’s wrinkled face, his wearied posture. He never spoke much, but seemed content. I remember that quite clearly. There was a calm about him.

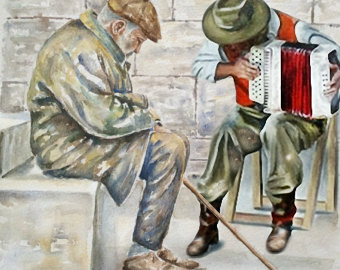

Yervant had a son named Albert, who was blind. Albert was, I think, about 38 years old when I first met them. They would often walk together around town, sometimes pass through our boutique, and Albert would play the accordion as they walked. He always seemed to have his accordion with him.

They were immigrants living in Tehran; they were strangers in a new world. But Yervant was an ordinary man, a friend of my father’s—that’s how I knew him. I would later learn that an ordinary life was all Yervant ever wanted. I was working with my father in Tehran when I first met them. I was about 18 years old and the year was 1960.

I sometimes imagine Yervant as a young man, long before he came to Tehran—before my father or I ever met him. I try to picture his home in Baku, Azerbaijan at the time, and what his neighborhood might have looked like. I picture bustling streets and open shops. I can see Yervant among the crowds, walking the streets as he would in Tehran, but not yet accompanied by Albert and his accordion. I imagine he was happy then, full of purpose and ambition.

Yervant was still a young man when the Russians came. It was around 1920 when the Red Army crossed the border, and it wasn’t long before they occupied much of Armenia and Azerbaijan. It was spring when they came, but the change of seasons was hardly noticed. Everything would change that year.

It happened suddenly and then gradually, this change. Yervant would talk about it occasionally when I knew him. He would say the Russian occupation was like a stranglehold on Baku, slowly choking out opportunity, dignity and then freedom. Life was very hard, he’d say. He wouldn’t say much more than that, but he’d say it slowly and pause as he said it, his mind clearly burdened with memories and images of the past.

Years turned into decades and home became prison in Baku. When Albert was born, Yervant told me it was like hope had been returned to him. Now that I am older and I have children myself, I know that feeling. But for Yervant, it was just a feeling. It was a feeling that came with the birth of his son, forever restrained by the reality of his surroundings.

Albert was around three when Yervant decided to leave Baku. Yervant had dreamed of another life for years, and now, decades later, a gift from his father brought new promise. I imagine Yervant sitting at home as he planned his journey, Albert at his side, his father’s gift on the table. The gift was a five-carat diamond, and I imagine it sitting there on the table, staring up at Yervant. I can see that hope he felt in Albert reflecting brightly off the diamond in front of them, a tiny sparkle in the darkness.

Yervant wrapped the diamond in chicken intestines and swallowed it just before arriving at the border. He knew the guards would take anything of value. They even took his suitcase and its contents—their last change of clothes.

They could never return home, but home had slipped away from Yervant years ago. They had no home, only each other, and now, the vast empty unknown. So there was Yervant, old and weak but with hope in his eyes, standing at the checkpoint with Albert at his side, a five-carat diamond sitting in his belly.

When they arrived in Tehran, Yervant sold the diamond with the help of my father, and gradually, sale by sale, piece by piece, he found his way. Yervant was a very old man, but in Tehran, when I knew him, he was young again.

Albert had opportunity for the first time in his life. He had joy. He could walk, anywhere he wanted and play any song he knew. Albert was always with his father, playing that accordion everywhere he went.

Yervant was an ordinary man in extraordinary circumstances. He had risked everything to give Albert the simple, ordinary life he never had. For the first time in a very long time, the future was something to look forward to. I often think of the two of them and their journey. I see them walking, the border behind them, the sun rising on the horizon. I picture Yervant with nothing but that diamond in his belly, and Albert, who could see nothing, with a vision in his mind.